Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

Fare enough: A systems view of ticketing and fare evasion on Melbourne’s trams, from bell-punch to myki

Ring out the old

The establishment of Melbourne’s electric trams from 1906 by new operators came with a new ticketing system, while MTOC persisted with the bell-punch system on its cable trams. All the disparate new operators [4] introduced essentially the same system – issuing of numbered paper ‘flimsy’ tickets by conductors on the tram. The fundamentals of this system would last for a little over ninety years, until the switch to Metcard in 1998.

Flimsy tickets were printed on thin paper stapled into blocks of one hundred tickets, perforated below the staple so that conductors could easily remove individual tickets in succession from each block. The choice of paper was important, as conductors had to carry in their bags sufficient tickets of each type to cater for an entire shift. When considering the heft of a bagful of pennies, any factor that could reduce the weight carried by conductors was welcome.

Sample flimsy tickets issued by the M&MTB before the introduction

of decimal currency in 1966.

Sample flimsy tickets issued by the M&MTB before the introduction

of decimal currency in 1966. - From the Melbourne Tram Museum collection. Photograph by Noelle Jones.

Tickets were issued for single trips, as there was no provision for multi-trip tickets. Each tram route was divided into sections of approximately one mile, and graduated fares were charged depending on the number of sections to be travelled. This required conductors to develop detailed knowledge of the routes, both in terms of the section boundaries and locations of cross-streets and significant landmarks.

Conductors were issued with manual ticket punches, each of which made a unique hole pattern when used to validate a ticket. Each ticket punch was numbered, the number cross-referenced with the hole pattern in a central register, as well as recording the conductor to whom it was issued. The hole was used as a visual cue by ticket inspectors to identify if a ticket was issued by the conductor on the tram. The portion of the ticket that was validated by the hole punch were the numbered portions down the long sides, indicating in which section the ticket was issued, together with the direction of the journey – ‘in’ for a journey towards the city, or ‘out’ away from the city.

M&MTB conductor’s ticket punch for use with flimsy tickets.

M&MTB conductor’s ticket punch for use with flimsy tickets. - From the Melbourne Tram Museum collection. Photograph by Noelle Jones

Tickets were issued to the conductor in blocks, each flimsy ticket in the block consecutively numbered. The conductor was required to maintain a running journal, recording the lowest ticket number on each complete or partially used block at the beginning of each trip. Passengers boarding at termini were well used to the sight of conductors logging ticket numbers into their journals. As the longest tram routes could consist of ten sections, up to twenty different types of tickets – including both full and concession fare – were required to be tracked by the conductor.

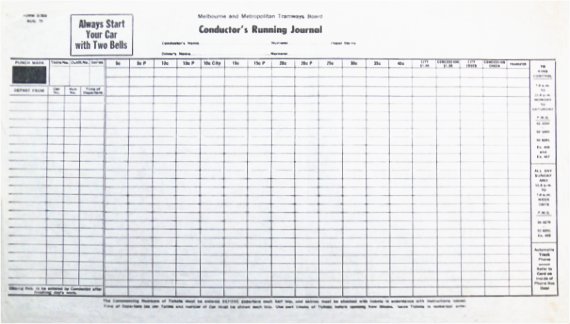

Blank form for M&MTB conductor’s running journal.

Blank form for M&MTB conductor’s running journal. - From the Melbourne Tram Museum collection. Image by Russell Jones

When an inspector boarded a tram, using the information from the running journal together witth the current location of the tram, he could validate passengers’ tickets using a combination of the section validation plus the ticket number. This system provided a robust capability to minimise the prospect of fare evasion, with only two real weaknesses:

- Need for two man crews. The standard Melbourne W class tram design required use of two man crews – driver and conductor – for normal operation. While this was not a major problem on heavily patronised routes, it was a significant disincentive for the M&MTB to operate electric trams on services projected to be lightly patronised. Only a small proportion of trams in Melbourne were suitable for one-man operation, and then only on lightly trafficked routes, or on all-night services. The result was that operation of the flimsy ticket system on Melbourne W class trams was more expensive than other contemporary ticket systems, such as the ‘fare collection box’ [5] used on many one-man Birney and Peter Witt cars in the United States. However, one man crews required trams fitted with expensive automatic doors and interlinked ‘dead man’ control systems, which were not fitted on the few remaining Melbourne W class tramcars until the late 1990s, and even then the W class was unsuited for one-man operation as the driver was unable to observe passengers’ compliance with ticketing requirements due to the central location of the doors.

- Difficult to monitor passengers in crowded trams. Minimisation of fare evasion required vigilance on behalf of the conductor. This could be problematic, especially on crowded peak-hour or football services [6]. A partial solution was implemented by use of two conductors on trams on heavily loaded sections, or alternatively by conductors at nominated city tram stops selling tickets to passengers prior to boarding, particularly during the evening peak. However a comprehensive solution for this problem was never devised.

At end of shift, the conductor would pay in the takings to the revenue clerk, who would reconcile the money against the running journal and the remaining tickets, providing an effective control against employee fraud. The only real option the conductor had for committing fraud was to resell discarded tickets, a practice that was known as issuing ‘flying canaries’. This would require the conductor to pocket immediately any money obtained by issuing the ‘canary’.

Conductors of the Fitzroy, Northcote and Preston Tramway Trust at

Preston Depot, circa 1920. Note the conductors’ bags with ticket

wallets.

Conductors of the Fitzroy, Northcote and Preston Tramway Trust at

Preston Depot, circa 1920. Note the conductors’ bags with ticket

wallets. - Photograph courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

The flimsy system had one significant advantage over the bell-punch system, in that the passenger had legal proof of purchase in the form of a flimsy ticket. It evolved with the introduction of the multi-ride ‘Day Tripper’ ticket introduced by the M&MTB in the 1970s allowing unlimited rides on trams and tramway buses. This was followed in the 1980s with the successor to the M&MTB – the Metropolitan Transit Authority – introducing zonal multi-ride systems with both daily and two or three hourly tickets for use on all forms of Melbourne public transport. However, these innovations required no significant operational changes to the flimsy ticket system, as both types of tickets were issued and validated by conductors punching out the date of issue with their ticket punches.

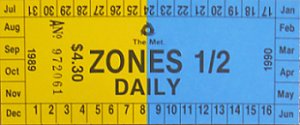

Metropolitan Transit Authority daily ticket valid for Zones 1 & 2.

Metropolitan Transit Authority daily ticket valid for Zones 1 & 2.

- From the Melbourne Tram Museum collection. Image by Russell Jones

Footnotes

[4] The new electric tram operators were:

- 1906 – Victorian Railways and North Melbourne Electric Tramways & Lighting Company

- 1910 – Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust

- 1916 – Hawthorn Tramways Trust and Melbourne, Brunswick & Coburg Tramways Trust.

[5] In 1909 T.L. Johnson of the Johnson Farebox Company patented one of the first registering fare boxes suitable for deployment in ‘pay as you enter’ one man tramcars. Over the next several decades, registering fare boxes were successfully deployed on thousands of Birney, Peter Witt and PCC trolley cars in North America, enabling widespread use of one-man crews even in periods of heavy patronage. They were never used by the M&MTB.

[6] The M&MTB operated special services to and from Victorian Football League (VFL) games scheduled on Saturdays between the months of April and September. These additional services were scheduled to align with the start and end of play at each ground serviced by the relevant tram routes. The following grounds were well-serviced by adjacent tram routes, with some having additional trackwork or sidings designed specifically to handle football crowds.

- Lakeside Oval (South Melbourne)

- Junction Oval (St Kilda)

- Western Oval (Footscray)

- Melbourne Cricket Ground (Melbourne, Richmond)

- Victoria Park (Collingwood)

- Fitzroy Oval (Fitzroy)

- Richmond Oval (Richmond)

- Glenferrie Oval (Hawthorn)

- Windy Hill (Essendon)

- Princes Park (Carlton)

- Arden Street (North Melbourne)

The only non-Melbourne based team – Geelong – also had its home ground served by Geelong’s tramways from 1912-1956.