Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

Tramway ANZAC: James Richard Pilmer

A long road

In 1916, Jim Pilmer was working for the Melbourne Tramway Board as a shedman at the Victoria Bridge cable tram depot. Jim was a local Brunswick lad, born in the suburb on 1 November 1892 to John Simpson Pilmer and Elizabeth (nee Parish) Pilmer, and was living with his mother at 328 Victoria Street, East Brunswick. He was the fourth of seven children, with five brothers and one sister. His father was an immigrant from Dundee, Scotland, while Jim’s mother was born in Ararat, in country Victoria.

Shedmen were responsible for local maintenance of the cable trams. This would include brake adjustments and replacements, lubrication of moving parts, minor body repairs, and most importantly, maintenance of the cable grip. A shedman would also drive the draught horse that pulled cable trams in and out of the depot. Major maintenance of the cable trams was carried out at the workshops in Nicholson Street, North Fitzroy.

In October 1916, Jim made the decision to enlist in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) for overseas service. His younger brothers Charles (Charlie) and Frank had volunteered for service with the AIF in January 1916 and September 1914 respectively, and would survive their military service.

The Pilmer family prior to the First World War. At rear: David, Ann, James and Frank. In front: John Pilmer, Charles and Elizabeth Pilmer.- Photograph courtesy of Joanna Campbell.

He wasn’t a big man, being only 5 feet 6 inches tall, and of a slight build. Like many of his comrades, he had the fair hair and skin and blue eyes of his British ancestors. Before the relaxation of the physical standards for enlistment in June 1915, Jim would not have qualified for army service, and he had indeed been rejected at a previous attempt to enlist.

At the time of his enlistment, the campaign for the first conscription plebiscite was being fought, as the number of volunteers was not keeping pace with Australian casualty rates. Prime Minister Billy Hughes was under pressure from London to introduce conscription, forcing young men to join the army. There was substantial opposition against conscription within Parliament and his own party, so Hughes decided to seek the backing of the electorate.

This was a bitter political fight, with battle lines largely drawn up on a sectarian basis – Catholics opposing the measure, while many Protestants supported the Prime Minister’s proposal to introduce conscription.

Jim signed up at Royal Park on 27 October 1916, the day before voting on the conscription plebiscite was conducted. His religion on the attestation form was given as Presbyterian, and he nominated his mother as next-of-kin, as his father John had died five months previously.

One of the reasons for his enlistment was that Jim wanted to be seen as a volunteer, not a conscript.

The plebiscite failed narrowly, and in the political fallout the governing Labor Party split, with Hughes’ followers forming a new party with the conservatives.

Meanwhile, Jim began his initial military training at Royal Park, before he embarked for England on HMT A7 Medic on 16 December 1916 at Port Melbourne. The Medic was a passenger steamship of the White Star Line, built in 1899 for the Britain to Australia service, and impressed as a troopship for the duration of the First World War. It had also been used as an Australian troopship during the Boer War (1899-1902).

The Medic sailed in convoy from Australia under the escort of HMS Cornwall, a Monmouth-class armoured cruiser of the Royal Navy, together with the troopships Port Lyttleton, Orontes, Burma, Medee, Orsova and Kenilworth Castle. The convoy sailed via Durban, Cape Town and Sierra Leone.

Jim managed to go ashore at both Durban and Cape Town, going to a performance at the Cape Town Tivoli theatre. He also noted the strangeness of apples being sold at 2/6 per dozen rather than by weight, as was the case in Melbourne.

On sailing from Cape Town on 16 January 1917, Jim was placed on submarine watch duty – 4 hours on and 8 hours off – and issued with a rifle and ammunition. An outbreak of meningitis had occurred on board, and the troops were paraded every day for application of an antiseptic throat spray as a prophylactic measure. However, Jim’s deck sergeant died of the disease. This did not interrupt the regular entertainment of boxing matches, or of a scheduled dance – Jim did not attend the latter, as he was on guard duty, although he remarked that it would have been a sombre affair without any girls in attendance.

The convoy arrived at Freetown, Sierra Leone, on 29 January 1917, after crossing the equator four days before. Unfortunately for Jim, the troops were not permitted ashore. Instead, in what had become a time-honoured ritual, the locals rowed out to the troopships on bumboats, selling fruit – oranges, bananas and coconuts – to the soldiers. Jim sampled both oranges and bananas, and although the skins of both were green, found them very sweet.

The voyage north to Britain was characterised by frequent changes in direction – known as zig-zagging – to avoid German U-boat attack, together with stringent anti-detection measures. All the portholes were kept shut, and the glasses painted over, to prevent transmission of light. Smoking was forbidden on deck at night, and lifebelts were ordered to be worn constantly, except when eating and sleeping. Even then, they were to be kept immediately at hand.

Jim disembarked in Plymouth on 18 February 1917, and was transported to a holding camp at Sutton Mandeville, Wiltshire, on the Salisbury Plain. While there he was able to see his brother Frank, who was stationed at Hurdcott Camp, about 6 kilometres away. Jim remained at Sutton Mandeville until 12 March, when he was transferred to 4th Australian Training Battalion at Codford, about 19 kilometres northwards, for intensive training in the essentials of trench warfare.

Once his training was complete, he embarked on a cross-Channel ferry at Southampton on 22 May 1917 and arrived at the major British base in France at Étaples the following day. From there, he was moved up the line until he was marched into the 14th Australian Infantry Battalion on 11 June 1917, as part of the 23rd Reinforcements for the battalion.

At that time, 14th Battalion was decisively engaged in the Battle of Messines Ridge, which lasted from 7 to 14 June, so Jim entered the front lines of the Western Front in a baptism of fire. The 14th Battalion was widely known for its fighting prowess and was known by many as “Jacka’s Mob”, after Lance-Corporal Albert Jacka, who was awarded the Victoria Cross for an action at Gallipoli while serving in the battalion and was subsequently awarded the Military Cross and bar for actions on the Western Front. At the time of Jim’s service, Jacka had been commissioned as a captain, and was commanding D company of 14th Battalion.

Most of Jim’s front-line experience consisted of actions in the 1917 Ypres campaign, more commonly known as the Battle of Passchendaele, which was fought from 31 July to 10 November 1917. In later years, he talked little of his wartime experiences, although he did recount the experience of seeing a large artillery shell landing only a few feet away from him. Jim remembered the terror of waiting for the shell to explode, but it was a dud round. He also mentioned that he received a slight whiff of mustard gas while he was on the front lines, which gave Jim an intermittent cough that he retained for the rest of his life.

Jim also vividly remembered hearing German troops talking and moving around in their trenches, only a short distance away from the Australian lines. He found it incredible that the enemy were so close.

On 23 August 1917, Jim was promoted from Private to Lance-Corporal.

The next major actions 14th Battalion fought were the Battles of Menin Road (20-25 September 1917) and Polygon Wood (26 September to 3 October 1917).

Jim was severely wounded on the first day of Polygon Wood, receiving six bullet wounds from a machine gun. He was hit in the thorax, abdomen and right thigh, the last wound breaking his femur. He was carried by stretcher-bearer to the Regimental Aid Post, before being taken by a field ambulance unit to 3rd Canadian Casualty Clearing Station a short distance behind the lines. He was evacuated the same day to 26th General Hospital at Étaples, where he would remain until 10 December 1917.

The bullet that broke his thigh was not removed, as it was judged too close to his sciatic nerve to safely extract, as accidental damage to this nerve would render Jim unable to walk. This bullet would cause Jim ongoing health problems during the remainder of his life, as occasional pressure on the nerve would render him temporarily unable to walk due to crippling pain. The remedy he used was to massage the bullet away from the nerve – no doubt a very uncomfortable experience.

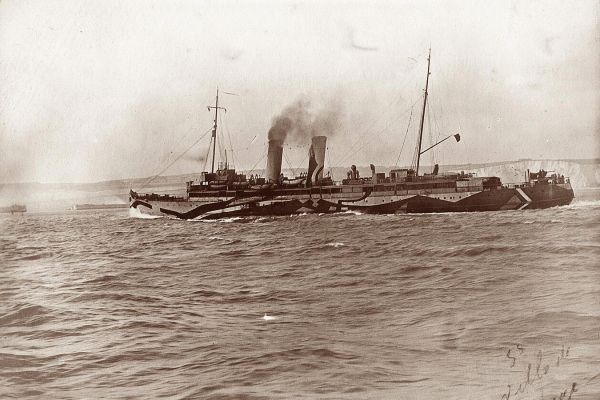

On 10 December 1917, he was taken by the Belgian fast ferry TS Ville de Liège [1] across the Channel back to England. Shortly after leaving Calais at 11:45am for Dover, a pair of destroyers turned the Ville de Liège back to port due to U-boats in the area, delaying the normally hour-long crossing by an hour and a half. In Dover, Jim was immediately transferred onto an ambulance train, travelling directly to the 1st Western General Hospital at Fazarkley, a suburb of Liverpool, arriving on 11 December at about 1:00am in the morning. This hospital had developed an outstanding reputation for surgical treatment and rehabilitation of complex fractures of the femur. By this stage, the break between the two halves of Jim’s femur had mostly healed, so Jim’s treatment was primarily post-operative care and rehabilitation. He remained at the Woolton Auxiliary Hospital – an outpost of the 1st Western General Hospital – until 6 February 1918, when he was transferred to 3rd Australian Auxiliary Hospital at Dartford in Kent.

Belgian fast cross-channel ferry TS Ville de Liège in 1918. This vessel carried Jim Pilmer back to England after he was wounded. Photograph taken by Surgeon Sub-Lieutenant Beresford Richards RNVR, from the deck of the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Zubian.- Photograph from the collection of Jon Richards.

On 11 February 1918, he was released from medical care and given two weeks’ leave, some of which was spent in London. At the end of his leave on 25 February he reported to HQ 2 Command Depot at Weymouth and was assigned to the Montevideo camp.

This was a transit camp for Australian soldiers who were scheduled to be sent home, unfit for further military service. While there, Jim was caught trying to leave camp without permission on the morning of 22 March 1918. The following day he was charged with the offence of “Breaking Out of Camp”. He was admonished and had a stoppage of three days leave applied, but no further penalty was given, as his conduct up until that time had been assessed as good.

Jim needed some extra cash and asked his brother Frank to cable his brother David in Melbourne, requesting a loan of £5. This money was wired to him via Collin & Company (merchants specialising in the Australian and New Zealand trade), arriving the day before he attempted to break out of camp.

Jim returned to Australia on HMT A30 Borda, boarding on 5 April 1918. The Borda was a Peninsula & Oriental Steam Navigation Company line ship, built for the Australian emigrant service, and impressed for use carrying troops during the First World War. After arriving in Melbourne, he was discharged from the army on 17 July 1918.

Jim did not return to the tramways. He worked for his brother Charlie as a farm labourer for many years on the property ‘Cazner Rest’ in Farnham Road, Healesville, where Charlie ran a mixed poultry and horticultural farm.

He attended Dookie Agricultural College in 1919, going on a course on Mixed Farming and gaining a certificate. During the Depression, Jim actively sought jobs in Healesville, attempting to find employment, as the farm could not support both brothers. A contemporary job reference described Jim as being honest, trustworthy, energetic and obliging, judging him as worthy of holding any responsible position.

For over seventeen years while living in Healesville, Jim worked as a poll clerk and then assistant presiding officer at local election booths in both Federal and State elections.

In 1937 he was living at 53 Liddiard Street, Hawthorn. Jim fell in love with with Margreta (Greta) Rose Raines, who ran a boarding house on the corner of Glenferrie and Barkers Road, opposite Methodist Ladies’ College in Kew. They married on 26 October 1937 at Caulfield. Greta had an eighteen-year-old daughter named Ruth from a previous marriage.

Their only child, James (also known as Jim), was born on 2 June 1938. He remembers his father as a quiet, gentle man, with a good sense of humour, and considered him a good father. Of any words that could be used to describe Jim’s character, his son thinks the best would be ‘quietly determined’. Jim senior rarely talked about his war service, although he would march with his comrades of the 14th Battalion on Anzac Day. However, Jim never went to the following social event but would instead come home directly after the march.

During a visit to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, his son – then aged 11 – remembers seeing Jim standing silently before a large painting of the Battle of Polygon Wood, with tears running down his face. When he asked his father what was wrong, Jim replied, “That is a painting of the place I was wounded, on the same day I was wounded.”

Australian infantry attack in Polygon Wood. Painting by war artist Fred Leist (1919), showing a pillbox under attack by Australian troops of 59th Battalion led by Lt John Turnour. This was the painting that affected Jim Pilmer on a visit to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.- Image courtesy Australian War Memorial.

Jim was employed as a postman, working from Kew Post Office from 4 August 1941, until he retired at age 65 at the end of 1954. It was a long day, working from 6am to 5pm riding a heavy single-geared bicycle in all weathers, although there was a two-hour lunch break in the middle of the day. Jim cycled the mile home for lunch, and usually worked for an hour or so in his vegetable garden, before returning to work for the afternoon rounds (at that time suburban residences received two mail deliveries per day). By all accounts he enjoyed working outside.

During this period, the Pilmers lived at 35 Davis Street, Kew, initially renting the house, which is still in existence. When it came up for sale, they bought the property, with Jim’s brother Dave bidding at auction on their behalf.

His experience of hardship during both the First World War and the Great Depression left a deep mark on Jim’s beliefs. He insisted to his son that it was vital to obtain secure, well-paid employment – preferably with the government – as the world was a deeply uncertain place. Hence, Jim arranged for his son to leave school at the age of fifteen for a job with the Postmaster-General’s Department, as a trainee telephone exchange technician.

Later in his time with the post office, Jim was the senior postman at Kew, and was responsible for opening the post office for the early morning delivery of the mail truck. On those days when his leg was troubling him, he would send his son to the post office to open up. After the mail bags were delivered, young Jim would lock up the post office, and return home to return the keys to his father, before going off to school.

Senior

Postman Jim Pilmer on his bicycle in Kew, circa 1950.

Senior

Postman Jim Pilmer on his bicycle in Kew, circa 1950. - Photograph courtesy of Joanna Campbell.

When his health was especially troublesome, Jim senior would be admitted to Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital for care. However, he was refused partial disability payments related to a respiratory condition, as the Repatriation Department did not accept that he had been exposed to mustard gas – there was no record of him receiving treatment on his service record.

After retiring at the age of 65, Jim continued living with his wife and son in the house in Davis Street, Kew. The last time his son saw Jim was during his final illness at Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital. Jim’s last words to young Jim, as his son left the ward, were, “Good-bye, son.”

Jim died at the age of 74 on 23 March 1966 and was buried in Burwood Cemetery. He was survived by his wife and son.

Bibliography

Australian War Memorial (2018), Enlistment Standards

Australian War Memorial (2018), Conscription during the First World War

Australian War Memorial (2018), 14th Australian Infantry Battalion

Australian War Memorial (2018), Unit Diary – 14th Infantry Battalion

Keating, J.D. (1970), Mind the Curve, University of Melbourne Press

Liverpool Courier (1919), Liverpool’s Military Hospitals – The 1st Western General Hospital, 7 October 1919

Melbourne Tramway Board (1918), List of Employees Enlisted for Active Service to 30th June 1918, Sands & MacDougall Pty Ltd

National Archives of Australia (2018), Service Record – Charles William Pilmer

National Archives of Australia (2018), Service Record – Frank Pilmer

National Archives of Australia (2018), Service Record – James Richard Pilmer

P&O Heritage (2008), SS Borda (1914)

Pilmer, J. (2017), Every Contact Leaves a Trace, Openbook Howden Print & Design

Somerset & Dorset Family History Group (2018), The Anzacs who came to Weymouth

Sutton Mandeville Heritage Trust (2018), Sutton Badges

Thornton, N. (2018), TS Ville de Liège – Past and Present, Dover Ferry Photos

Other sources

Interview with Rev. Jim Pilmer (son), 22 June 2018

Interview with Rev. Jim Pilmer (son) and Joanna Campbell (granddaughter), 13 July 2018

Letter from Jim Pilmer to his mother, dated 16 January to 15 February 1917

Letter from Jim Pilmer to his mother, dated 14 December 1917

Letter from Jim Pilmer to his mother, dated 28 January 1918

Letter from Jim Pilmer to his mother, dated 30 January 1918

Letter from Discharged Soldiers’ Qualification Committee, dated 16 October 1919

Employment reference from W.J. Dawborn of Healesville, dated 6 July 1935

Retirement Letter from Postmaster-General’s Department, dated 11 January 1955

Footnote

[1] The TS Ville de Liège was famous for fast crossings of the Channel, due to its high-powered steam turbine engines driving triple screws giving it a top speed of 24 knots. It was converted for use as a hospital ship in May 1917. The high speed of the Ville de Liège made it difficult for U-boats to engage.