Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

Here comes the rain again: Melbourne tram shelters

Melbourne’s weather is notoriously changeable, indeed it is commonly claimed by residents that it can have four seasons in a day. Therefore, it is inevitable that intending tram passengers waiting for the next car to arrive at their stop will at some time get wet from the rain. All Melburnians have experienced the speed with which a cool change rolls up from the south-west, and been thoroughly soaked at one time or another. As a result, over the years the various tramway operators in Melbourne built shelters at tram stops, and a surprising variety of these still remain in use today.

When the first cable tram line was opened in partnership by MTOC and MTT (Melbourne Tramways Trust) in 1885, no tram shelters were provided. In this era, people dressed for the weather, and both the company and the trust believed that there was no requirement to provide shelter for their customers. Indeed, tram stops themselves were not well defined, so a key problem was in determining where any shelters should be placed. Besides, cable tram services were so frequent that no-one was left out in the weather for very long anyway.

In any case, all Victorian and Edwardian shopping strips came complete with verandahs bedecked in cast iron lace and other decorative work, which protected shoppers from both the rain and the sun. As these were the busiest locations for cable tram traffic, what need had MTOC to provide shelters to its customers? Furthermore, MTOC was a listed company, and shelters would not earn any revenue for its shareholders. Nor would the State Government spend money to the profit of such a company, when it was furiously devising schemes to access the profits generated by the cable tram system.

It was not until 1910, when the Prahran & Malvern Tramways Trust (PMTT) came into being, that tram shelters started appearing on the scene. This was primarily driven by the less frequent services provided by this outer suburban electric tramway operator, in comparison to those of the cable tram system. Passengers could wait for 15 minutes or more for a tram, a period within which they could get very wet.

Therefore, the PMTT undertook a program of building tram shelters at key points, particularly interchanges between the cable tram system and the PMTT electric lines. The largest and most impressive of these was at Victoria Bridge, but others existed at interchanges along St Kilda Rd. Four ex-PMTT tram shelters are still in use. Three are of a ‘verandah’ style and were built around 1915. Of a simple timber and corrugated iron structure, they feature decorative cast iron lace and Corinthian columns. These shelters are located at:

- corner of Orrong & Malvern Roads, Toorak

- corner of Orrong & Balaclava Roads, Caulfield North

- corner of Cotham & Burke Roads, Deepdene.

Former PMTT tram shelter at the corner of Dandenong and Hawthorn Roads.

Former PMTT tram shelter at the corner of Dandenong and Hawthorn Roads.

- Photograph courtesy of Heritage Victoria.

The fourth PMTT structure remaining is the oldest surviving tram shelter in Melbourne, located at the corner of Dandenong Road and Hawthorn Road. This shelter was designed by the architect of the PMTT, Leonard J. Flannagan, and constructed in 1912 at what was then the key interchange point for the nascent PMTT electric tramway system.

The shelter is constructed mainly of timber and has a half hipped roof with deep overhanging eaves. The small ‘gablet’ at each end has plain barge boards, the gable is faced with shingles and contains a louvred vent. The roof is clad in red asbestos tiles with a crested terracotta ridge terminated by scrolled terracotta finials. The hips have plain terracotta ridge tiles. The rafters are exposed under the projecting eaves, and the underside lined with boards. The walls are timber-framed with the upper panels (above the dado) lined with V jointed boards arranged diagonally. The lower panels (below the dado) are clad with vertical V-jointed lining boards on the internal face and shingles on the external face. The interior is sub-divided by timber partitions into four alcoves framed by simple timber brackets; each has a built-in bench seat made of timber slats. The seats face in all four directions.

This shelter is also listed on the Victorian Heritage Register.

Two tram shelters that were clearly influenced by this PMTT design, but on a much smaller and more austere scale, are located on route 70 (at the corner of Highfield & Riversdale Roads) and route 75 (Camberwell Rd & Smith St). These examples on former Hawthorn Tramways Trust (HTT) routes are clear evidence of cross-pollination between the two trusts.

The end of the MTOC lease of the cable tram system in June 1916 opened the way for wider provision of tram shelters, when an interim government body, the Melbourne Tramways Board (MTB), became responsible for the operation of the system — to be superseded in 1919 by the Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board.

Former MTB tram shelter at the corner of Macarthur Street and St Andrew’s

Place, East Melbourne, September 2008.

Former MTB tram shelter at the corner of Macarthur Street and St Andrew’s

Place, East Melbourne, September 2008. - Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

The first tram shelter built by this body appeared at the corner of Macarthur Street and St Andrew’s Place East Melbourne, just behind Parliament House. The Federal members occupying the stately building (as they would until the building of Parliament House in Canberra in 1927) had become tired of waiting in the rain for cable trams after late night sittings. Clearly, a gentle hint had been dropped in the ears of the bureaucrats of the MTB.

This tasteful structure was designed by Frank Stapley, architect and Melbourne City Councillor, and built in 1917. The style was based on Edwardian domestic fashion using timber construction and a slate roof. Given the prominent nature of the potential passengers, it was given the unusual distinction of a travertine mosaic floor, complete with an inlay of the MTB logo. The logo also appeared on the gable ends of this shelter. Visibility of oncoming trams from the interior was excellent due to the stylish windows, and the parliamentary passengers could rest their weary feet inside, well protected from the vagaries of Melbourne weather.

Tram shelter at the corner of St Kilda Road and High Street.

Tram shelter at the corner of St Kilda Road and High Street.- Photograph courtesy of Heritage Victoria.

In the same year, a similar shelter was built at the corner of St Kilda Road and Dorcas Street, but without the mosaic floor. A total of nine shelters of this design were built but only five survive till today, the two built in 1917 for the cable tram system together with those built in 1927 for the conversion of St Kilda Road to electric traction, one at Lorne Street and two at High Street. All have been placed on the Victorian historic buildings register.

Not so historic

With the growth in passenger numbers from the end of the Depression to the start of the Second World War, the M&MTB decided to invest in a low maintenance austere standard tram and bus shelter design. As a result, during 1940-41 the first four of the new design appeared at the following locations:

- Sydney Road & Bell Street, Coburg

- St Kilda Road & Bowen Crescent, South Melbourne

- St Kilda Road & Moubray Street, Melbourne

- Point Ormond omnibus terminus.

New 1941 shelter and RAAF serviceman, corner of St Kilda Road and

Bowen Crescent. Moreland-bound W2 322 in the background.

New 1941 shelter and RAAF serviceman, corner of St Kilda Road and

Bowen Crescent. Moreland-bound W2 322 in the background.- M&MTB photograph.

This welded steel design was to become widespread across Melbourne, painted in silver and green, and was built in large numbers at the M&MTB Preston Workshops until 1974. Construction of these shelters was funded on a 50:50 basis by the M&MTB and the relevant local municipality. However, in later years this standard design would prove to be vulnerable to vandalism, and passenger visibility was poor – even though later examples incorporated cut-out safety glass windows. As the aesthetics of the design won few friends, almost all were rapidly replaced. The only two that remain are on routes 55 (corner of Brunswick Road and Grantham Street) and 1 (corner of Park Street and Canterbury Road).

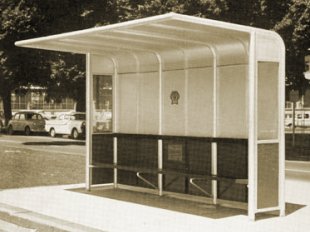

M&MTB standard steel tram shelter, 1969. Note the glass windows.

M&MTB standard steel tram shelter, 1969. Note the glass windows.- M&MTB photograph.

The renewal of Melbourne’s tramway system heralded by the re-election of the Hamer government in the early 1970s saw attention being paid to the tram shelter design as result of the need to match the modern appearance of the Z class tram design with something more aesthetically pleasing. Therefore, Preston Workshops began to build a new standard design of shelter from 1974, consisting of a welded steel frame and glass panels, and was designed by J Scholtz, the Assistant Workshops Manager. The new mustard coloured angular design was thought to be much more fitting street furniture for a modern city like Melbourne, and 25 were erected in various locations in that first year.

One of the features of the new design was that a transparent network map was stuck to the interior glass panel for passenger information purposes. This design, although simple, was quite successful and not unpleasing to the eye.

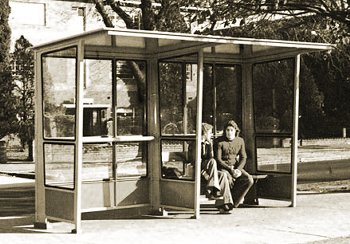

1974 design tram shelter.

1974 design tram shelter.- M&MTB photograph.

A few examples of the 1974 design shelter are still extant on the Melbourne tram network, although it is expected that they will be driven to extinction by the Adshel and JC Decaux families of shelters (described below).

The opening of the underground rail loop and the Museum railway station [1] saw an increase in passenger numbers wishing to catch the Swanston Street trams north to the University of Melbourne and beyond. The 1974 design was developed and extended in 1981 to a larger shelter incorporating a strong curve in the roof. In this it recalled some aspects of the old standard shelter design. Although effective from a functional viewpoint, it has to be admitted that it was not particularly attractive, due to cluttered nature of the framing required to hold the glass panels.

1981 design tram shelter at Museum Station, corner of Swanston and

La Trobe Streets.

1981 design tram shelter at Museum Station, corner of Swanston and

La Trobe Streets.- M&MTB photograph.

Fortunately this design was not to become widespread, and it no longer exists at the original site as result of the conversion of Swanston Street to a restricted traffic thoroughfare officially named Swanston Walk – a term which has not met favour with the public, who defiantly still know it as Swanston Street. However, one modified example of this design survives in South Melbourne at the corner of Whiteman Street and Clarendon Streets, where it is used to protect intending customers of the Colonial Tramcar Restaurant against the weather before they board their vehicle for a sumptuous repast.

Odds and sods

Two shelters that outlived their tramlines and remain to this day are the small corrugated iron and timber shelters on the west side of Beach Road in Middle Brighton, opposite Dendy Street and Kinane Street. These were built in the late 1940s to serve the Victorian Railways’ St Kilda to Brighton Beach line. This line was suffering from severe maintenance arrears from before the Depression, and the VR was keen to close it. However, it was still popular with passengers from this demographically influential area, who pressured the railways administration to improve the amenity of the line. VR caved in to the pressure, as it was much cheaper to build a couple of small shelters rather than to completely renew the line’s infrastructure. Unlikely as it may seem, these shelters survived the closure of the tramline in 1959.

One historic shelter that no longer serves a tram stop but still sees trams trundling by on route 75 is located at the football ground on Camberwell Road. This was provided by the HTT for football patrons, and is of classic timber design, serving supporters of the Camberwell VFA football club [2] from the post-match winter cold. Unfortunately, the club was not a dominant team in the VFA, losing the Grand Final to Yarraville in 1935 and Brunswick in 1946.

In later years the team succeeded in winning 2nd division premierships in 1979 and 1981, but the club collapsed in 1991 through lack of interest in the face of the national AFL competition. The disappearance of this local icon saw the reason for this tram stop also vanish, and the stop moved some fifty or so metres southeast to its current location outside a retirement home, where it is served by a 1974-style steel and glass shelter.

The rustic tram shelter still lingers, a reminder of different times when the football club was the social hub of the suburban universe, and a lightning rod for Saturday afternoon tribal loyalties.

What makes a good (and bad) tram shelter

The name ‘tram shelter’ is something of a misnomer. The buildings we are discussing do not shelter trams, but instead shelter people. However, common and accepted usage is that we call them tram shelters, as indeed the corresponding structures for bus routes are called bus shelters.

Before we plunge further into the varieties of tram shelter design extant in Melbourne, we should consider what constitutes a good tram shelter. Clearly, the design should not stray far from its intended primary function, which is protection of intending passengers from wind and rain, and to a lesser extent the harsh summer sun and daytime temperatures in excess of 30°Celsius common in Melbourne from December through to March.

Furthermore, a good tram shelter should have a number of secondary characteristics:

- It should be low in construction and maintenance costs.

- It should be resistant to vandalism.

- It should protect passengers from road traffic, either by construction or positioning.

- Passengers must be able to easily see approaching trams.

- It should enhance the existing streetscape, or at least not reduce the visual amenity.

- Space should be provided to allow for both adequate seating and standing room.

Let us examine a modern example of a tram shelter, which services the terminus (now known as a superstop) for most of the Swanston Street tram routes at the University of Melbourne, at the corner with Faraday Street.

Built in 2005, the overall concept and design was developed by Fooks Martin Sandow Anson Pty Ltd of North Melbourne. This is one of the busiest locations on the tram network, as thousands of students use this stop every weekday. Intense pedestrian congestion can occur at peak times, so the platforms demanded by legislative access requirements to low floor trams have been combined into a central island reminiscent of railway practice.

Key drivers in the design criteria were the necessity to cater for the shunting requirements of the terminus, particularly improving turnaround times, together with controlling pedestrian access and motor traffic flows in order to promote safety. The actual shelters on the island platform are steel and polycarbonate stylised tree canopies, reflecting the northern end of Swanston Street and the avenue of trees merging into College Crescent.

Clearly, given the important location of this facility, the design brief was such that it should provide a clear statement and enhance the somewhat ordinary streetscape at this site. However, when examining the shelters against the functional design criteria of good tram shelters, they are somewhat less than successful.

The steel and polycarbonate ‘trees’ provide no protection against wind, so in the not uncommon instance of driving rain, passenger protection is minimal. Furthermore, the polycarbonate roofing material provides no shade, so there is no shelter against the occasionally ferocious summer sun, particularly on those days when a strong northerly is blowing and the air temperature is like that in a blast furnace.

While no doubt the ‘trees’ are resistant against vandalism, provide excellent visibility of oncoming trams, are low maintenance and are well protected against errant vehicles due to their positioning, they were definitively not inexpensive.

It is fair to say that these ‘tree’ shelters are a triumph of appearance over function, and provide almost no shelter for passengers. Clearly, the whimsy of the architects and parties involved in the design (primarily the University of Melbourne and M>Tram [3]) was allowed to dictate the direction taken, rather than focusing on the functional requirements of a successful tram shelter.

The students and staff of the University of Melbourne will be getting wet for many years to come — unlike any politicians or public servants who may be using the 1917 shelter at Macarthur Street.

In stark comparison to the modern Swanston Street shelters, let us look at the rustic tram shelter serving Wattle Park Chalet in Riversdale Road (near Alandale Street). Designed by Alan G. Monsborough [4], the architect of the M&MTB during the period 1926-38, it was built in 1928 as part of the general development of Wattle Park undertaken in that year, together with the extension of the tram line from Warrigal Road to the current terminus at Elgar Road.

Set back into an earth embankment, it is built from native rough stone and secondhand materials from demolished cable tram buildings. As such, it fits perfectly into its park-style environment, fulfils all the key design functional criteria for a tram shelter, and is an undoubted success. Would we be able to say the same about those at the University of Melbourne? I think not.

One tram shelter design requirement that we have not discussed, which has only become more prominent over the last couple of decades, is the need to provide a sense of security at night, particularly to ensure that intending passengers feel safe and secure in patronising Melbourne’s tram system. This is best enabled by provision of excellent levels of lighting, which has been retrofitted to virtually all of the remaining older tram shelters.

An enterprising company called Adshel has stepped into the provision of tram shelters that addresses this very requirement, with the integration of high levels of lighting and illuminated advertising panels directly into the design. These shelters are owned by Adshel and funded by advertising revenue paid directly to Adshel, rather than via the tramway operator. This effectively outsources the provision and maintenance of tram shelters from the tramway operator, as well as providing a substantial improvement in the appearance of tram shelters and brightening the general streetscape at night [5].

A variety of shelter designs of modern and more classic appearance are available from this company, but all are based on modular components manufactured from powder-coated aluminium and toughened safety glass or polycarbonate, with integrated seating, together with space for shelter of prams and wheelchairs. The Adshel shelter designs appear on the former M>Tram routes.

A competitor to Adshel, JC Decaux, is also providing shelters on the Melbourne tram system. This company formed its alliance with Yarra Trams during the brief period from 1999 to 2004 when the urban system was run as a private duopoly, and covers the provision of both tram shelters and tramcar advertising. Similar design principles are used by both companies.

These shelters of various designs are now widespread around Melbourne’s tramway network, replacing most of the older shelter stock that was built up over the years.

However, shelters from both companies seem to be placed with more consideration of maximising advertising exposure to motor traffic than for the sheltering of intending passengers. In some locations, positioning of the new shelters on narrow footpaths has exposed their patrons to close proximity to heavy traffic. In addition, the large illuminated advertisements can occasionally prove distracting to motor vehicle drivers. It seems that safety was a secondary consideration when siting of the new shelters was decided.

Both of these street furniture providers have participated in the construction of superstops, combining use of their standard shelters with raised platforms adjacent to the tramline. The platforms, which are the same height as the new low-floor tramcars, enable easy access by wheelchair-bound passengers.

Collins Street ‘superstop’ with Citadis low-floor tram,

2004.

Collins Street ‘superstop’ with Citadis low-floor tram,

2004.- Photograph courtesy VicTrack.

Superstops have attracted significant criticism from the motoring public, due to the increased occupancy of roadway formerly available to motorists, usually resulting in the loss of an entire traffic lane. In addition, those superstops located in the centre of the road significantly restrict the flow of passengers to and from the tram stop by forcing them to use the ramps at either end of the platform. This design shortfall, made to increase passenger safety, increases pedestrian congestion around the tramcar and results in an increase to stopping times, slowing tramway services down.

Examples of superstops can be found at Federation Square, St Vincent’s Plaza, and all along route 109.

Other notable tram shelters

One of the most notable tram shelters in Melbourne is no longer in use: the Franklin Street signal box and tram shelter. This is a substantial brick rendered building built with an elevated signal box to control the terminus and junction at the top end of Swanston Street; formerly the busiest terminus on the entire network. However, with the removal of the main Swanston Street terminus to Melbourne University, and the replacement of manned signal boxes by driver operated points, this building has fallen out of use. Unlike the Sydney system, there were few tramway signal boxes in Melbourne; the other major ones being located at St Kilda Junction and Batman Avenue, both of which no longer exist.

The Batman Avenue signal box was also combined with a tram shelter, and was located at the Batman Avenue terminus opposite Flinders Street Station that was used by Wattle Park (route 70) trams, and was also used by Burwood trams (route 74) prior to 1965 and Prahran trams (route 77) prior to abandonment of that service in 1993. The development of Federation Square saw it demolished in 1999, in combination with the diversion of Batman Avenue services into Flinders Street.

The advent of driver operated points and sophisticated traffic light systems have removed the need for this type of combined signal box and tram shelter.

Bibliography

Adshel

website

Fooks

Martin Sandow Anson website

Heritage

Victoria Online Register

M&MTB Annual Reports (1920-1982)

Footnotes

[1] Museum railway station is now known as Melbourne Central, due to the removal of the Museum to Carlton Gardens and the development of the Melbourne Central shopping mall and office complex.

[2] Footypedia has detailed information on the Victorian Football Association (VFA) and the Camberwell Football Club.

[3] M>Tram was owned by National Express, a UK-based company, and was the franchised operator of half of Melbourne’s tram network from 1999 until the parent company abandoned the franchise in late 2002, when it was run by receiver/managers on behalf of the State Government until 2004. Yarra Trams became the sole operator of trams in Melbourne in April 2004, when it took over accountability from M>Tram for the remaining half of the network.

[4] The driveway into Wattle Park is named in his honour.

[5] However, the illuminated advertising in Adshel and JC Decaux tram shelters can occasionally be distracting for motor vehicle drivers, as attested by the author from time to time.