Melbourne Tram Museum

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Twitter

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Facebook

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Instagram

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Pinterest

- Follow Melbourne Tram Museum on Tumblr

- Subscribe to Melbourne Tram Museum's RSS feed

- Email Melbourne Tram Museum

Fare enough: A systems view of ticketing and fare evasion on Melbourne’s trams, from bell-punch to myki

Since mass urban public transport began in Europe in the early nineteenth century, operators have struggled with a common problem – fare evasion. Over the years, Melbourne’s tramways adopted a variety of different systems to minimise the problem of passengers not paying their fares.

The problem was recognised in the Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company’s Act (1883), which empowered the Company (MTOC) to construct and operate the Melbourne cable tramway system. MTOC was also authorised to make by-laws governing the operation of the tramway, as was already the case for the Victorian Railways. Section 35 of the Act provided for fare evaders to be fined up to forty shillings for each individual offence, while section 36 allowed any servant or officer of the Company to detain offenders against the Act or relevant by-laws without warrant.

Policeman, conductor and gripman in front of cable tram at Toorak

Road terminus, c1889. Note the strips of cardboard pinned to the conductor’s

jacket lapels, for use with the bell-punch to register fares.

Policeman, conductor and gripman in front of cable tram at Toorak

Road terminus, c1889. Note the strips of cardboard pinned to the conductor’s

jacket lapels, for use with the bell-punch to register fares.- Photograph courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

To place the level of fines in context, the Harvester Judgement of 1907 set the male basic wage for an unskilled labourer at seven shillings a day. Clearly, fare evasion was seen as a serious issue, even before the first of Melbourne’s trams ever turned a wheel. However, despite this punitive start, under the various enabling Acts the fine for fare evasion on Melbourne trams would remain at forty shillings for more than seven and a half decades from its 1883 inception.

Nonetheless, the main emphasis of the MTOC fare system was on minimising revenue loss through employees defrauding the company rather than addressing fare evasion by passengers. When a cable tram conductor accepted a fare from a passenger, he [1] used a bell-punch to clip a hole in a piece of card pinned to his lapels, a different colour card being used for each different fare value. The bell-punch would store the clipped card, increase a mechanical counter and register the acceptance of the fare by ringing a bell – hence the name. The bell would not ring unless a card of the precise thickness as the lapel card was placed in the jaws of the punch.

Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company bell-punch, front view.

Melbourne Tramway & Omnibus Company bell-punch, front view. - From the Melbourne Tram Museum collection. Photograph courtesy Noelle Jones.

No ticket was issued to the passenger, except for transfer tickets that allowed passengers to change trams for specific routes, usually only within the Melbourne Central Business District. If the passenger did not hear the registering of the fare by the ringing of the bell-punch, he or she was advised to complain to an inspector. The inspector would subsequently arrange for that conductor to be placed under observation by plain clothes inspectors, in order to try to catch him in the act of pocketing fares.

The inspectors were also tasked with detecting and charging fare evaders, however prime accountability for ensuring passenger compliance with regard to ticketing was assigned to the keen eyes of the tram conductor.

At the end of each shift, the conductor would surrender his takings, the lapel cards and the bell-punch to the revenue office at the depot. A clerk [2] would open the combination lock on the bell-punch and remove the coloured confetti, reconciling them against the counter, the punched lapel cards and the takings. Any discrepancy between the takings would be deducted from the conductor’s pay. If the conductor consistently recorded discrepancies, he would be subject to disciplinary action, up to and including dismissal without notice.

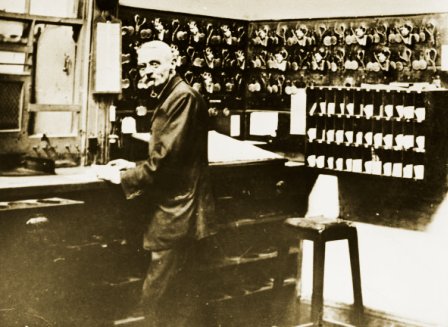

A tallying clerk employed by the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company

to reconcile takings at the end of conductor’s shifts, c1890.

Note the bell-punches on the wall behind him.

A tallying clerk employed by the Melbourne Tramway and Omnibus Company

to reconcile takings at the end of conductor’s shifts, c1890.

Note the bell-punches on the wall behind him.- Photograph courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

The Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board [3] withdrew the bell-punch system from the Richmond cable tram line in November 1921, and progressively removed it from all other routes by the end of the following year. The replacement ticketing system was known colloquially as ‘flimsies’.

While the bell-punch system worked well in managing employee fraud, it did not really address the issue of passenger fare evasion, as there was no way – other than relying on the conductor’s memory, or the sworn evidence of one of the company inspectors – of validating whether a passenger had paid a fare.

Footnotes

[1] No woman was ever employed as a conductor on a Melbourne cable tram.

[2] The role of tallying clerk was the only role within MTOC that was filled by female employees.

[3] The Melbourne & Metropolitan Tramways Board was the operator of Melbourne’s tramway system – both cable and electric – from 1919 to 1983, taking over from the temporary Melbourne Tramways Board that managed the cable tramway system after the end of the MTOC lease in 1916. It was replaced by the Metropolitan Transit Authority in 1983.